Wounded Warrior Project

Serving those who serve, Reporter Monica Holland

A Fayetteville dentist, his hunting buddies and a supportive community in Duplin County offer prime deer hunting to wounded soldiers

The sun pours out of the west like a soft golden shroud over the woody stubble and scrub on Brian Willson’s Duplin

County land. From the second story of his hunting tower, one can see 300 yards to the Goshen Swamp, as well as the

corn pile beneath a feeder and the elevated blind in between.

“I got a great

deal on the land,” Willson says, “and my idea was that when you get a deal like that, you try to spread it

around.” The purple domes of turnips, a result of Willson’s efforts to attract deer with food plots, break

the soft soil around acres of brush and wild habitat. Squint hard and a path emerges, a dry road over the wetlands

leading to more stands, an oasis of clover and countless cervid tracks.

“I got a great deal on the land,” Willson says, “and my idea was that when you get a deal like that, you try to spread it around.”

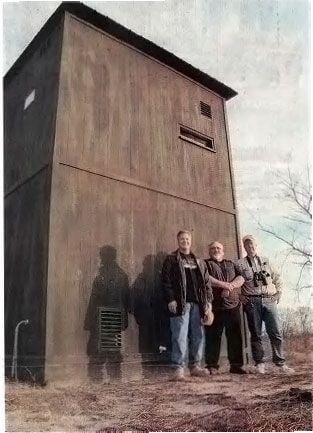

Brian Willson, Linwood Coleman and Guenther Labann stand in front of a two-story hunting blind on Willson’s Duplin County property that is equipped with a chairlift for Wounded Warriors.

The Fayetteville dentist, who has earned the prestigious title of Diplomate of the International Congress of Oral Implantologists, shared his fortune with hunting buddies Linwood Coleman and Guenther Labann, along with his three sons. But when he invited his friend Jimmie Lewis, a wheelchair-bound, former-host of WFNC’s Swap Shop radio program, to hunt the land he realized that he had the opportunity to offer something special. Lewis helped Willson design a handicapped accessible hunting lodge with a ramp, widened doorways hard floors and a specially equipped bathroom. The idea snowballed.

Willson contacted the Wounded Warriors Project and began working with the group to offer hunts on his land. “One of the things that keeps me connected with the wounded warriors is that I treat a lot of the family members,” he says. “I’ve treated married women who have lost their husbands. I see all the dependents – wives and kids.”

The idea of giving back inspired Willson to go beyond his camouflaged golf cart with netting turned mobile-hunting blind. He built a 4×6-foot elevated blind, not with the usual ladder, but wide stairs for ease of use. The blind was destroyed by Hurricane Irene, so Willson decided to up the ante. He rebuilt that blind, this time with the wider wall not facing the north. And he took on a bigger project.

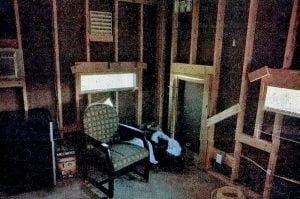

In August 2008, he began the construction of a two story, 12-foot square blind. He had a chair lift installed by Acom, and he cut shooting windows out of three of the four walls upstairs. He added a futon, carpet, television, microwave, toaster oven and air conditioning.

Community support

When word got out about his efforts to offer hunts to Wounded Warriors, business owners and

neighbors came through with reduced rates and property easements to lessen the burden on Willson – not that he

would ever call it a burden to work so hard at making his property such a fine hunting spot.”

“The more time I have, the more stands I can build. And the more stands I have, the more trips I can do,” Willson says.

He takes groups of four to-six warriors out four times a year to hunt from any of his seven stands spanning more than 300 acres of habitat.

He buys discounted corn from a neighbor, dropping 50 pounds on nine feeding areas every week. Southland Rental offered heavy equipment at reduced rates to help with the building. Airco-Reco Heating and Cooling installed his electrical work at no charge. Kenansville Equipment has given him free use of a Kubota RTV. Roads were built at low rates thanks to Mike Jernigan.

“Whenever I. tell people what our mission is here, they really don’t charge full price,” Willson says. But he puts in the work to make it count. With help from Labann, Coleman and others, the land has become a home to sizable bucks, wild hogs, turkeys, beavers, small game, coyotes and bears. They only hunt the deer, though. And all non-warrior hunters are allowed only to shoot 8-pointers and up.

Guenther Labann and Dean Isaacs of the Wounded Warrior Battalion pose with a buck Isaacs shot on a hunt on Brian Willson’s Duplin County farm.

The game, however, isn’t the only goal. “It’s amazing how you can see the happiness at this table and around the fire pit after the hunts,” Coleman says. “They’ll never be repaid, but at least they know somebody cares. “It’s a feeling like I’ve never had to be out there with these guys.” Added Labann: “For the guys who come out here, it’s really a break. It also lets them know that on the outside, there are people who appreciate what they are doing.”

Staff writer Monica Holland can be reached at [email protected].

Local landowner provides respite for Wounded Warriors with advanced hunting accommodations.

Story and photos by Todd Wetherington

MOUNT OLIVE – When Brian Willson speaks about the work that has come to define the free hours of his life over the last four years, the respect and reverence he feels for the men and women involved is written in the hushed tone of his voice and the wide-eyed, uncomprehending gaze of a man whose life has led him down a path he never expected to travel.

Willson’s trip into the unknown began in 2007 when a patient, a professional woodcarver, paid a visit to Willson’s dental clinic in Fayetteville. The man related to Willson that he was in need of a new wood sander for a project he was working on making 300 walking sticks with compasses attached to the handle for men and women involved in the Wounded Warriors Project (WWP), a group that seeks to honor and empower members of the U.S Armed Forces who have incurred service-related injuries on or after September 11, 2001.

The mission of WWP is to raise awareness about the needs of injured service members, while helping them to aid and assist one another. The group also provides unique programs and services to assist injured service members.

In addition to addressing physical injuries, WWP also features a Combat Stress Recovery Program to help returning members deal with the emotional and psychological stress incurred as a result of combat and the mental strain of war.

According to the group’s website, with advancements in battlefield medicine and body armor, an unprecedented percentage of service members are surviving severe wounds or injuries. For every U.S. soldier killed in World Wars I and II, there were 1.7 soldiers wounded. In Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, for every U.S. soldier killed, seven are wounded.

Combined, there have been almost 42,000 injured in the two conflicts-nearly 32,000 injured in Operation Iraq and nearly 10,000 in Operation Enduring Freedom.

Taking his cue from advice offered by his patient, Willson decided to become active in WWP by offering service members involved in the program a place to hunt on property he owns in Duplin County, a secluded stretch of 150 acres set in the rural farming community along Furney Jones Road southeast of Mount Olive.

“I’ve always been into hunting, and my three sons hunt, so it just seemed like a natural way for me to be able to help,” remembered Willson, during a recent interview at the hunting site.

At the time, said Willson, he was in the process of building a hunting lodge on his property. After making the commitment to become involved in WWP, Willson said he decided to turn the building into a gathering place for the service members.

“We put it up in about ten weeks. We came in and made everything handicap accessible and we put in central air, a fridge, a stove, and a microwave,” said Willson.

The lodge, which is painted in camouflage colors, is also reinforced with walls of solid concrete.

“It ‘s not going to go anywhere during a hurricane,” Willson observed.

Turning his attention to means by which he could make the hunting experience both easier and more enjoyable for WWP mem-bers, Willson decided to build a series of hunting stands equipped with spe-cial features to help injured service members navigate the two story structures.

“I guarantee you we have the only stand in Dup-lin County with a 200 amp meter box,” he smiled.

The most unusual few tune of the stands, which are built on concrete slabs and take three to four months to build, is a chairlift which can be used to carry disabled service members from the bottom floor up to the second story, where a series of rectangular slots are cut out of the walls to provide spaces to shoot from.

The gun slots offer a clear view of the woods below, and an ideal vantage point for hunting deer. Wilson said the chairlifts were provided by a company called Stairlifts. which is run by Charles Knapp, a former Army physician who served during Operation Desert Storm. Willson said Knapp sold him the chairs for half price and divided the payments into two installments.

According to Willson, the company is able to provide chairlifts to Wounded Warrior members in their homes for no-cost.

“Many of theses families are on a financial thread. so to get these chairs at no-cost is a big factor,” said Willson.

The stands also offer a few modern day amenities, such as a coffee maker and a ceiling fan. Willson said he eventually plans to install bathroom facilities on the ground floor as well.

A typical outing, said Wilson, begins with him picking up the WWP participants at 5:00 a,m. and taking them to the lodge. After returning from hunting. the service members are treated to a meal of deer stew and vegetables. After the sun sets, Willson said everyone typically gathers around a large camp fire to relax.

Willson said he has two to three hunts a year and normally takes out four to six individuals at a time. The next hunt is planned for November.

Though only one stand is completed at present, it is actually the second one built by Wilson and his team. The first one, several hundred yards across the woods, was toppled by winds from Hurricane Irene,

“I was sick when I saw what had happened. said Willson. “There were a lot of hours spent working on that stand.”

Looking over the remains of the first stand, Wills or explained that the entire project has been an exercise in trial and error.

“Im not a construction guy; this has been a learning process for me. I just have to take it one step at a time and learn as I go.”

Willson said he hopes to salvage the stairs and part of the walls of the original stand. arid have a new one completed within the next few months .

Joining Willson in the project was his longtime friend, Guenther Labann. who worked beside Willson On both the hunting lodge and tree stand projects. ” its really rewarding to work with the guys,” stated Labann. “Out here in the country, people come out of the woodwork to help.”

As proof of Labanns words, Willson ran through a list of neighbors, busi-nessmen and friends who have come to his aid since the beginning of the ambi-tious project.

Dan Penny, a farmer from Beulaville, has pro-vided Willson with corn which he uses to attract deer and prepare meals for the WWP members. seiling it to him at cost while charging nothing for ship-ping or labor.

“If he was helping them, I felt like I could help him out,” said Penny about his involvement. “I think its a great thing; there’s a lot of people who don’t have the finances to do what he’s doing. We should do something for them (veterans), because they’ve done a lot for us.”

Willson’s neighbor, Dean Cooper, a Vietnam Veteran who served in the war from 1967-1968, was generous enough to deed an easement to Willson in order to facilitate access to the property where the stands would be placed .

Cooper, who suffers from prostate cancer due to his exposure to the de-foliant Agent Orange while serving in Vietnam, said it was his hope that the expe-rience of the WWP veter-ans would be far different than his own .

“Its a very good thing Brians doing. When I came back from Vietnam. we had people spitting at us and calling us baby killer. I think its different with the people coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan. there seems to be a little more sympathy.”

Though the publics re-actions may have altered, Cooper said some things are all too familiar.

“When these guys come back injured, the govern-ment puts them out. The benefits they’re getting aren’t as good as a lot of people think,” he stated.

According to Willson, two other Forney Road neighbors. Ray Bell and Mike Chambers have also played roles in the project: Bell by allowing him to cut through his property while constructing the stands and Chambers by agreeing not to spray manure at his hog farm during the weekends that Willson hosts WWP members.

Another friend singled out by Willson was Jimmy Rich ofAirco-Reco Heating and Cooling in Kenansville. According to Willson, Rich did all the electrical work on the stands, charging Wilson solely for the cost of the materials. When he sent Rich a check for $200. remembered Wills or, Rich sent it back a month later.

“Those guys have been terrific,” said Willson. “They didnt have to do any of this, Im an outsider and a lot of times people in small communities are very protective and distrustful of anyone not from the area. But everyones truly gone out of their way to help.”

Speaking about the men who have come to his lodge in wheelchairs and crutches, sharing their stories around the kitchen to be in their hunting lodge, Willson and Labann both shook their heads as they described the mental and physical strength of the soldiers theyve come to call friends.

“These guys sit around the table, and it’s almost like they’re telling camp fire stories,” said Willson. “One guy has a broken back, another one’s on crutches, some have post traumatic stress syndrome-most of these guys are pretty badly injured. They tell us their stories, sitting around the table. They are beginning a whole new chapter in their lives, transitioning out of military life. Its a whole new world for them.”

“It’s really heartwarming; when theses guys come out theres no sob stories,” stressed Labann. “Theres never anyone feeling sorry for himself, it’s all uplifting.”

Willson said he’s seen the stress placed on the families of injured service members first hand.

“Being in Fayetteville, a lot of my patients are in the military. I see a lot of wives with husbands in the service. And sometimes the husbands are gone or in-jured and they’re left alone with three or four kids They go through a lot.”

Just getting permission to go on the hunt can be an ordeal, said Wills or. “They need three different clear-ances to come: physical, psychological, and legal. Theres a lot of paper work involved. The medical is the main one: if they can be transported and can fire a gun, then there’s no problem with them hunting with us.”

As to the resolve of many WWP service mem-bers. Willson noted, “Everyone’s a unique story.”

All these guys are tough as nails. We recently met a guy who told us he has to make a decision about whether to keep his arm, which is severely damaged, or have it cut off and be fitted with a prosthetic.

“Everyone has their own everyday worries, but the things theses guys go through are something else entirely. It really puts things in perspectives.”

Todd Werherhtgton may be reached at [email protected] or 910-296-0239.